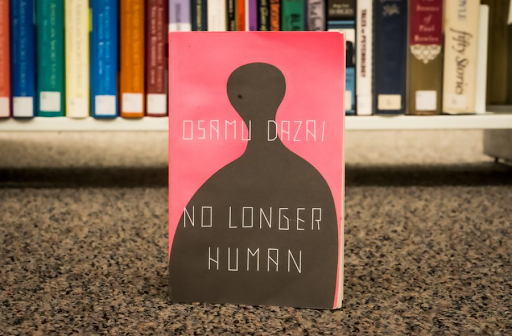

No Longer Human Book Review: The Saddest Book I Have Ever Read

Trigger Warning: This book & review contains themes of depression, substance abuse, and mental illness.

The Japanese novel “No Longer Human”, published in 1948, tells a timeless, introspective story of mental illness.

When I first read No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai in an attempt to branch out beyond American literature, I didn’t expect for it to impact me as much as it did.

The semi-autobiographical story told by the late Japanese author Osamu Dazai, is written in three sections called notebooks – each one increasingly more grim than the last. No Longer Human was Dazai’s last complete work before he committed suicide in 1948.

This story depicts a lot of Dazai’s own life through the eyes of the main character, Oba Yozo, from the momentary bits of tenderness in his life to his failures with love. Dazai portrays a horrifyingly realistic perspective into the mind of a man who struggles with alienation, depression, and addiction in search of a way to be human. The book holds a specific focus on the alienation of childhood depression, detailing Oba’s course of life in a time when mental illness wasn’t ever discussed out loud. I found a strange relation with the feelings of “otherness” that Oba describes. No Longer Human was published in post-World War II Japan and has extremely poignant descriptions of this time and culture.

When Oba was a young child, he found it difficult to comprehend the essence of human nature and how to connect with others, always disconnected from those around him – a trait that stuck with him for the rest of his life. Oba acted as the “class clown” in order to deceive his family & friends of his true feelings of depression and fear. When studying abroad in Tokyo and meeting a man named Horiki, he was introduced to a whole other world. His life quickly plunged into one of smoking, drinking, and tragedies of all kinds – resulting in a numbing self-reflection submerged in great anguish. Oba is constantly plagued with his feelings of guilt, shame, and resentment, and while having moments where he feels secure and happy – he inexorably falls back into the hollows of loathing and despair. These recurring instances made Oba’s downfall seem inevitable as I read on.

As the main and by far the most intriguing character in this novel, Oba tends to strike you with his constant struggles with deciphering what it means to be human and how to attain that association – creating a unique atmosphere I haven’t seen in other books. Despite his numerous faults, Oba still emerges as a very pitiable character that I couldn’t help but feel for.

In spite of how cynical and depressing this book is, I believe that everyone should read it at least once in their lives. The book’s thoughtful portrayals and veiled parallels from the main character’s fiction to the author’s dark reality could help shed a light on the thought process of those with this mental illness. There aren’t many literary works that convey depression in such immersive detail.

Overall, I would recommend this book to anyone who thinks they are prepared for it, or more precisely, to those who are prepared to gaze into the mirror of mental illness and face what stares back.